“Any discussion of the psychosocial aspects of low vision must acknowledge the formidable task of defining the [blind and] partially sighted population…People with low vision are, without question, heterogeneous with regard to degree, type and amount of remaining vision… age, onset of the condition… educational status, receipt of various services; and adjustment or maladjustment to the condition.” - John L. Morse

Apart from the physical challenges imposed by their visual impairment, individuals who are blind or have low vision must also face the constant challenge of psychologically and socially adjusting to their disability. Tuttle (1987) defines adjustment as the process of responding to life’s demands and stresses. While there is no direct relationship between impairment and psychopathological disorders (Harrington & McDermott, 1993), the heterogeneous nature of conditions and the possible differences in family life, education, social and economic status suggest that adjustment is idiosyncratic – it is personalised, peculiar and dependent on the life experiences of the individual. The following paragraphs will present several psychosocial aspects of blindness and low vision. Following one of the key themes in this thesis it will argue that the education of both the self and society is essential for positive adjustment. It will expose some of the general misunderstandings about visual impairment and demonstrate how these are partly responsible for the perpetuation of myths and misconceptions regarding the character and abilities of this population. In direct relation to this thesis it will argue that confidence and self-esteem are deeply connected to the ability to navigate and wayfind and should be regarded as constructive elements of the ego and personality manifested in different types of introverted or extroverted behaviour. Wherever possible arguments will be backed by past and current research in socio and abnormal psychology as well as specific case studies recorded by the author during the years he lived and worked at the Royal London Society for the Blind as a life-skills tutor.

The age of onset blindness or impairment can have significant effects on the affective development of individuals (Rosa, 1993). During the years the author spent working as a life-skills teacher at the RLSB some students who were congenitally blind or visually impaired observed that they were actually happy by the fact that they were born with an impairment and not lost their vision later in life because they felt they were not missing anything as they had no idea what it actually meant to see. Jill a blind student went as far to remark that she preferred being blind than visually impaired. She felt that the total loss of a sense was more comforting than having “something that did not function properly.” The view that being congenitally impaired (usually congenitally blind) is easier to come to terms with is often mentioned in the literature (Morse, 1983; Warren, 1984) but should not be over generalized. Affective development is individual and context dependent. Clearly there will be differences in the adaptation of congenitally and adventitious blind or visually impaired. Time is an important variable to consider. First, a congenital impairment forces an almost automatic acceptance of the condition. An adventitious impairment on the other hand is often accompanied by an element of surprise, trauma and depression that requires a certain accommodation period. Trauma and depression can affect both the individual and the family at least an an initial shock. Training or experience should also be considered, as functional and positive self-development will depend on the individual’s mastery of the other senses and/or residual vision for the organization of information and active participation in society.

Social classifications

Man is a social being and a person’s sense of identity is dependent on the manner it is perceived by others. We adapt and live based on constant feedback from the family, community and friends. Feedback allows for the control and organization of actions and relationship to others and provides checks (approval or apprehension) on behaviour. The delivery of feedback is crucial and can have an important effect on one’s sense of identity, self-concept and esteem. Individuals who are blind or visually impaired must rely to a greater extent on auditory and tactile cues. While this type of information still allows for the discerning of moods, emotions and can help the individual make inferences about a person’s character and emotional state; it lacks the visual complement afforded by facial expressions. Morse (1983) observed that the blind are not very accurate at deducting and judging personal characteristics by voice alone. For this reason, communication must be clear, reliable and as redundant as possible to avoid mix-ups from both the sighted and the visually impaired.

In some individuals who are blind or have low vision the normal appearance of the eyes (and the individual in general) can lead to a certain amount of confusion and in some cases to general mistrust, suspicion or doubts about the degree of the impairment. Roger, one of the author’s most extreme cases lived through his early teen years under scorn, disrespect and was often taken for a lazy, unmotivated and careless man. In his early teens Roger complained to his mother that he could not see very well. Together they visited a series of ophthalmologists who failed to diagnose his condition, many of them saying that they could not find anything wrong with his sight. His performance at school declined and some of the teachers went as far as to say that Roger was lying about his vision to make up for his lack of interest in school activities and his low grades. In reality Roger could barely read from the blackboard. Roger was finally diagnosed with macular dystrophy but the absence of any blindisms, mannerisms and the fact the he was not required to use glasses perpetuated some of the prejudice from both his teachers and classmates. Roger went on to complete school and university with minimal assistance. He developed a series of techniques that in time included the use of low vision aids such CCTV and other type of magnification tools. He now has a successful post at the department of transport.

Roger’s story is both shocking and a true example his mother’s trust and indefatigable persistence believing in her son until his condition was diagnosed and cared for. It also a reflection of Roger’s own character – his courageous and hardworking nature. Despite his impairment and years of shunning, Roger never gave up on his education and eventually was able to secure a good working post. Stories such as this, are the exception rather than the rule. These days, ophthalmologists are quite efficient in detecting visual conditions and introducing technical aids. Nonetheless, low vision continues to be filled with contradictions. The fact that an individual is not wearing eyeglasses, carrying a symbol or white cane or the fact that the eye forms the outside appears to be unimpaired can lead to some terrible confusion. Society must be educated – wisdom elevates, ignorance kills.

The way we are perceived however only partly reflects who we are. As we have seen in the previous section there are a variety of impairments each limiting different aspects of vision. The word limiting should not be taken lightly. Limit is related to vision not to behaviour in general. Morse (1983) notes that loss to the lower half of the visual field usually implies difficulties in mobility but does not mean that the individual cannot watch television, do a crossword puzzle or work in front with a computer. Similarly, loss to the right field is associated with difficulties in reading (reading print in western countries requires a left to right eye scanning) but does not imply a lack of independence in terms of mobility or spatial awareness. Low vision manifests itself in contradictory behaviours. It is not uncommon to see the student with low vision who cannot read from a blackboard but is able to comfortably ride a bicycle or the individual who can watch television from a distance but continuously stumbles on a step or curve. This lack of understanding often balloons low vision to total vision loss or at least leads to assumptions about general ability disproportionably discrediting the individual. We must seek to understand these limits and resfrain from making false assumptions and generalizations that can have disabling effects on one’s self-conception. The same is the case for blindness where the uninformed assumes that either individuals who are blind have more acute senses or that because of their loss there are incapable to independently cope with life in society. It is important to note that there are several strategies used by educators and orientation and mobility specialist that can be used to compensate for low vision irrespective of the location or amount of the visual deficit.

The manner in which people are labelled and classified can have important implications for in their social and personal lives. At the heart of Durkheim’s sociology of knowledge (Durkheim & Mauss, 1963) is the notion that classification is social in origin and a categorization and extension of reality. Low vision has often been described as a neither fish nor fowl phenomenon. Visual loss is many times perceived as an all or nothing occurrence. For some reason, blindness seems like an easier concept to understand than low vision. We can close our eyes; walk about the room and to a certain extent place ourselves in a situation of total visual absence and some of the difficulties associated with it. It is much harder to conceive of a situation of partial visual loss – and even more so of the different conditions and types of visual loss. Blindness in this sense is understood and classified by contrast to seeing. Low vision on the other hand falls in a sort “grey” and uncertain area.

An incorrect classification imposes an inaccurate reality. Classifying a person with low vision as blind can have serious limiting effects as individuals become uncertain of the extent of their residual vision and overall abilities. Labelled as blind individuals can sometimes act as if they were blind and eventually begin to see themselves as blind. The inaccurate labelling of low vision can also lead to wrong decisions in the part of parents. Lack of knowledge regarding the condition can force parents of children with low vision to adopt educational strategies that do not take advantage of residual/functional vision. It can also lead to a type of over caring where the parent spoils the development of the child hampering his/her independence. Sometimes children are placed on specialist school solely based on their acuity level while their functional vision would still make them competent candidates for mainstream education.

Passing

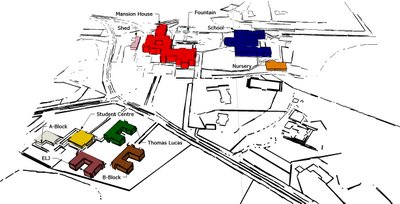

Passing occurs when an individual with low vision pretends to be blind or sighted in order to take advantage or cope with a situation. During his years at the RLSB the author had the opportunity to watch two cases of such theatrics whose relevance to this section make it worth reporting. The first case is that of Alex a teenager who enrolled with Dorton College as registered blind student. When asked about his visual condition Alex replied that he was blind and had no vision. He moved around with a white cane, used speech software in the computer and was learning Braille. He considered himself and was considered by others as a blind student. Alex was eventually asked to participate in the author’s study and was screened to be part of the blind group. During one of the tasks, when the subject is asked to construct a tactile model of the RSLB campus using scaled cardboard pieces, the author noticed that instead of asking for the pieces to be handed to him Alex was actually grabbing them from their location on the table. This behaviour was very odd considering it was impossible for Alex to reach directly with such dexterity.

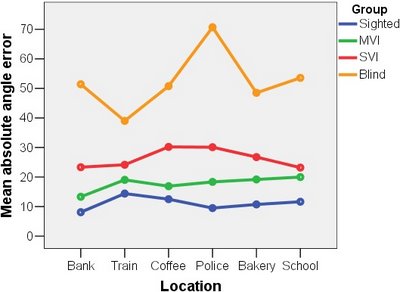

Alex was not blind. After inspection of his personal file, the author discovered that he was diagnosed with Leber’s optic neuropathy (see section on eye conditions) when he was fifteen. Alex was passing as blind in order to claim a higher disability/incapacity living allowance. Free loading is not our primary concern especially if we consider that the actual claim difference is neither substantial nor extravagant. What is particularly upsetting is the fact that when passing as blind, Alex was educated as a blind person surrendering the functional aspect of his vision. Before the sudden onset of his condition Alex was a talented catoonist but passing as blind forced him to give up almost completely his sketching. Alex was not discarded from the research but re-classified as severely visually impaired (see chapter 7). He participated in both experiment and his overall high performance is further evidence of his ability to functionally use his residual vision. He is no longer viewed or considers himself a blind person and is currently working on strategies to make the best out of his residual vision.

The transition from education to the workforce is perhaps one of the biggest challenges faced by individuals who are blind or have low vision. That society discriminates should not come as a surprise especially in the labour market where the order of the day is the maximization of utility. Although the government intervenes and labour laws are constantly being updated, most recently laws on ageism; preconception, presuppositions, biases and prejudices still have their way in the work domain. It is in such situations that passing may be beneficial. David a former Dorton College student spent almost six months applying for a variety of jobs. The only replies came from fast food joints and cleaning services. David automatically turned these down. Taking a job means that he would have to give up his disability/incapacity allowance and as it turned out the wages offered were lower than what he was already receiving. Although the author does not condone this type of action, it is at least demonstrative of the difficulties in transition and to some extent the cult of poverty that many times surround disability.

David was upset. Not a single company, office or factory replied and he began to doubt his skills. At this moment he decided to pass as sighted. The author would be lying if he said that the situation really improved. What did happen was that David was at least able to secure two or three interviews, one of these with British Telecom (BT). Unfortunately, after passing most aptitude tests with BT and at the verge of being offered a job as a repairman, David was turned down because he did not have a driver’s licence. While it will never be known if passing is what secured his the interview it is at least clear from his experience with BT that as long as he was fully sighted he was able to secure a job. Presently David is working as cook at a school’s canteen. The irony lies that during his unemployed days the author hired David as his research assistant. He was trained, to interpret video data to enter it in Geographic Information Systems Software (ArcGIS) a somewhat advanced skill for a college graduate and something that would surely afford him a decent wage in the job market.

Psychosocial adjustment, self-concept identity & self-esteem

The overall psychosocial adjustment of individuals with disabilities has been a topic of much interest but of considerable disagreement. The adjustment to life in a world that is essentially visually biased is a complex feat and almost impossible to generalize. Adjustment is inevitably tied in with issues of independence, sufficiency and control and will vary from person to person influenced by their character, previous experiences and support network. Research on psychosocial adjustment has incorporated a variety of questions ranging from the impact of progressive or immediate visual loss, anxiety, the inability to work, avoidance and bullying to the role of support networks such as friends, families and charities. Morse (1983) reviewed several studies on the psychosocial adjustment of children with low vision. He concluded that children with low vision tend to be more unsettled by the limits of their vision, when compared to those whose handicaps are more severe and that their parents seem to be less understanding of the disability than those of blind children (Bateman, 1962). These results were echoed by Peadboy (1967) who found that children with low vision tend exhibit with more frequency underachieving like behaviours, fatigue and are more prone to emotional problems.

More recently a study by Kef (2002) on the psychosocial adjustment and the meaning of social support for Dutch teenagers (aged 14 to 24) with visual impairments revealed that majority of these teenagers had high-self-esteem, that they seemed to feel happy, not lonely and that most had accepted the implications of their impairment. No significant differences were found between blind and individuals with low vision (both severe and mild), although the scores for the severely visually impaired tended to be more negative. Interestingly, no significant differences were found between these groups and sighted adolescents. Sighted adolescents however, tended to have a larger network of family and friends although individuals who were blind or had low vision were satisfied and believed they received enough support from parents and peers.

An important aspect of psychosocial adjustment is the development of a positive self-concept. Self-concept can be defined as a set of attitudes individuals hold about themselves that help shape their identity, self-image, and esteem and what conditions their expectations and motivates their behaviour. It has important implications on the personal professional and social life of an individual. A positive self-concept is usually associated with the ability to cope and overcome the consequences of a disability. It gives an individual a positive outlook on life, satisfaction and commitment. Jake, another of the author’s student, was diagnosed at birth with retinopathy of prematurity and lost his sight when he was three years old. His parents were divorced, and he lived with his mother who happened to be unemployed and an alcoholic. It seemed as if Jake’s future was determined; his ability to flourish and overcome his disability hampered by his socioeconomic situation and his mother’s lackadaisical neglect. Fortunately the opposite occurred. Jake’s situation forced him to become independent at a very early age. The lack of support meant that he had to learn how to fend for himself and quickly develop life-skills to cope with life in a sighted world. With a remarkable hunger for achievement, and a constant strive for superiority Jake attended mainstream education and was able to properly function in society. As it turned out Jake was one of the best performers in the author’s experiment. His ability to represent space and ease of movement was a true reflection of his audacity and confidence. His mobility officer having once remarked that “watching Jake move is like watching poetry in the making.” Jake left the RLSB two years ago and now lives with his partner and future wife who happens to be sighted.

Individuals differ in how they accept their disability. In some cases, the inability to cope leaves the individual feeling detached from the general society. In other situations, individuals detach themselves because they feel they cannot fit in or are being pitied by others. Negative self-concepts are usually associated with isolation, depression and mental and health problems (López-Justicia, 2006). The author had the unfortunate experience of dealing with two separate cases of students whose emotional state was so low that they were contemplating suicide. Details are omitted in order to preserve teacher/student confidentiality. However, and without chancing any conclusion these individuals held several characteristics in common that were reflective of their negative self-concept. They were both blind from birth (retinopathy of prematurity), had few friends, preferred life at college than at home and tended to spend most of the time by themselves. They usually felt that they were not good enough and that the teachers and the “sighted society” communicated with them because they pitied them.

There is no general agreement as to whether the self-concept of individuals who are blind or have low vision differs from that of the sighted. Results from several studies summarized in Morse (1983) vary as to the positive and negative attitudes the blind and visually impaired children and teenagers have towards themselves. Jervis (1959) concluded that there were no significant differences between the blind and the sighted, while Meighan (1971) found that the blind tend to view themselves extremely negatively and Bauman (1964) that the partially sighted have a greater degree of anxiety, insecurity and loneliness. More recently, Sack (1996) found that individual with low vision perceive themselves more negative, expressing feelings of isolation and unjust fault when compared to the blind or sighted and Freeman et al., (1991) found that in many cases individual with low vision tend to reject services that would be beneficial because they did not want to be labelled as blind. Here it is worth noting that these all these experiments used different scales in their assessment of self-concept.

López-Justicia et al., (2001) conducted several studies to determine whether Spanish children and adolescents with congenital low vision had lower self-concepts than did their sighted peers. They found that children between 4-11 years of age with low vision tended to score lower on all dimensions of self-concept when compared to the sighted children. Interestingly differences were not significant in terms of family, physical appearance, self-worth, security and classroom. This lack of significance appears to be an indicator that these children are receiving and value the support from their family, classroom and peer networks. For children aged between 8-11 years significant differences with the sighted were found in regard to the relationship with classmates and relationship with parents. While the relationship with classmates was viewed as more negative (difficulty in making new friends or feel valued by their friends) the relationship with parents was regarded as strong and empowering. Finally, results for the adolescent (aged 12-17) group revealed significant difference with the sighted only in terms of physical self-concept with individuals with low vision scoring considerably lower than their sighted counterparts. These results are somewhat expected as it is during this age that individuals begin to pay more attention to their physical appearance.

Love is not blind, at least for most part of the time. Our exterior appearance and the body language that usually accompanies are responsible for many of the first impressions other have about us and unfortunately first impressions tend to last. It is not uncommon to find among blind and visually impaired teenagers those who think of themselves as unattractive, because of their weight or a physical deformity. The author was faced with many situations where he had to counsel many of his students regarding their exterior appearance in an effort to boost their self-esteem. Self-esteem is one of the key components of self-concept as it relates to the value that individuals place on their own characteristics, qualities, abilities and actions (Griffin-Shirley & Nes, 2005).

Here again, results from past research on the self-esteem of individual with low vision and blind are contradictory. In a longitudinal study , Shapiro et al., (2005) found significant gender differences on visually impaired children perception of competence. Males were found to be more positive at the beginning of summer camp when compared females. These difference however, tended to disappear across time with female competence levels increasing at the end of camp. The improvement in the perception of competence, for both males and females, across times emphasizes the role of friendship and participation in the development of a positive self-concept. That fact that these children were at a summer camp and constantly interacting with camp counsellors is further evidence that these individuals through their instruction verbal praise and ongoing feedback can function as guides and to some extent role models. Rosenblum (2000) found that although many teenagers had negative feelings about their visual impairment, the extent of this negativity varied among individuals with some deliberately hiding their visual impairment while other expressing unhappiness but understanding it as a part of life. Finally, a study by Huurre et al., (1999) on the social support and self-esteem among Finnish adolescents with visual impairments found similar results. In addition, Griffin-Shirley & Nes (2005) found no significant differences in the level of self-esteem and empathy between sighted and visually impaired preadolescents. These authors argue that the lack of difference may be related to recent trends in education and inclusion as well as greater awareness of the disability by the family. Sacks (1996) observers that in many cases low vision devices can be used to show an individual the extent of their functional vision and enhance self-esteem. He notes however, that these should be carefully instituted as they are highly conspicuous and may draw unnecessary attention to the individual.

So... this is it. My last day in the UK but definitely not my last post about the UK. Leaving this afternoon to Barcelona and will have quick pit stop by Montreal. The really exciting news is that I am moving to Santa Barbara at the beginning of next year. This will blog will continue to be linked with the Royal London Society for the Blind pretty much until I finish writing my dissertation. I will write more about Santa Barbara when I get a few minutes to sit down. Lately my life has been all about packing :)

So... this is it. My last day in the UK but definitely not my last post about the UK. Leaving this afternoon to Barcelona and will have quick pit stop by Montreal. The really exciting news is that I am moving to Santa Barbara at the beginning of next year. This will blog will continue to be linked with the Royal London Society for the Blind pretty much until I finish writing my dissertation. I will write more about Santa Barbara when I get a few minutes to sit down. Lately my life has been all about packing :)